Written By: Ritu Nakra, B.Ed (HI), LSLS Cert.AVT; Mary D. McGinnis, LSLS Cert.AVT, PhD candidate; Ellen A. Rhoades, Ed.S., LSLS Cert.AVT

INTRODUCTION

“Oh! your child isn’t talking yet? Don’t worry. Some children start talking later than others.”

“My friend’s brother started talking late.”

These are some common responses that parents hear when their young child is not speaking. Parents rarely think their child might have a hearing loss.

Although there is widespread agreement that early identification of hearing loss is important for long-term positive effects, neonatal and infant hearing screening is not yet implemented across all countries (Singh, 2015). Children are often diagnosed when someone in the family observes that the child is not speaking or reacting to sounds. This observation usually occurs when the child is around two years of age or older. If the child has moderate to severe hearing loss, identification may be further delayed until as late as three to four years of age. Since 90-95 percent of children with sensorineural hearing loss are born to parents with typical hearing, hearing loss is often the last thing parents expect.

Late-diagnosed children: a neurological emergency

The brain is the major organ of hearing. Ears are just the entry point, or a “doorway,” through which sound travels to the brain. Given that speech and understanding spoken language are acoustic events, audition is the easiest, most direct, and most effective sense by which typical communication skills are learned. In general, basic listening and language skills are developed during the first two years of life, when the brain has maximum neural plasticity (Kuhl, 2011).

Hearing loss during the first two years of life results in significant brain changes. Cross-modal re-organization occurs; this means that the brain’s reliance on auditory information is replaced by reliance on visual information which can work against the development of any residual hearing capacities (Campbell & Sharma, 2016). When the brain re-organizes itself, the typical processes of developing listening and spoken language (LSL) skills are lost. Hearing loss, then, is a “doorway” problem (Flexer & Rhoades, 2016).

When children are diagnosed at a later age, the family is often thrust into major emotional turmoil (Phillips, Worley & Rhoades, 2010). The child’s prime period of typical growth in speech and language has been lost and typical developmental processes have been altered; hence, the need for late-identified children and their caregivers to learn LSL skills with the assistance of LSL specialists experienced in the implementation of auditory-verbal strategies. When auditory-based intervention is initiated at ages later than two years, LSL specialists implement remedial auditory-based intervention strategies for children with hearing deficits.

Additional challenges for older children

Many developmental domains are dependent on hearing and language acquisition. Some of those domains include academic knowledge and socio-emotional skills that include Theory of Mind (Ketalaar et al, 2012). To bridge the learning gaps, auditory-verbal practices—a holistic intervention—incorporates the characteristics of infant-directed speech (IDS) to facilitate focused and sustained auditory attention as well as spoken language learning. IDS promotes a strong auditory-based foundation that, in turn, enables the transition of many children to the educational mainstream, whereby typical literacy skills may be developed (Mayer & Trezak, 2018).

Can IDS ameliorate cross-modal re-organization?

Can cross-modal reorganization be reversed with older children who receive appropriate auditory input later in life? Research indicates that it is possible to amend or mitigate cortical re-organization in adults, even after long periods of deafness (Stropahl, Chen, & Debener, 2017). When caregivers use IDS, research reveals improvements in children’s language learning (Wang, et al, 2017). There are improvements in the child’s auditory attentional skills which, in turn, prime the child’s statistical learning capacities considered essential for language learning.

IDS is an interactive style of speaking to infants that makes use of simpler words, much repetition, a higher and more varied range of pitch, and a slower rate of speaking (Rhoades, 2020a; Rhoades, 2020b). This exaggerated type of emotionally-charged turn-taking with infants is typically used by caregivers in western cultures. Research findings indicate that features of IDS highlight certain aspects of speech (e.g., an emphasis on fundamental frequency and increased vowel space), rendering those features more salient for auditory learning (Bornstein et al., 2020).

IDS can help children transition from visual processing to auditory processing (Dilley, et al, 2020). Fortunately, there is an exquisite match between features of IDS and auditory-verbal strategies used by LSL specialists which provides the basis for intervention, no matter the child’s age. Strategies used with a late-identified child are similar to those used with an early-identified child, except that daily opportunities for parents to use IDS may need to be contrived in a more thoughtful fashion, since older children may not spend as much time with parents as they do at school or with friends. Opportunities must be maximized to strengthen the auditory basis for listening, language, and speech development. Relative to early-identified children, older children typically need more time in transitioning from visual to auditory processing.

LSL strategies for using IDS with older children

Using LSL strategies (Fickenscher, Gaffney, and Dickson, 2015), the components of IDS are made audible for late-identified children.

- Minimize adverse listening conditions: Excessive background noise contributes to complex acoustic environments that, in turn, significantly degrade speech perception, language comprehension, and such cognitive skills as auditory attention and processing speed (McMillan & Saffran, 2016; Blaiser, et al, 2014). Moreover, adverse listening conditions significantly increase the need for effortful listening which can be exhausting for children with hearing differences (Peng & Wang, 2019).

Environmental modifications (e.g., rugs and cloth coverings for windows and hard furniture) help dampen reverberation. TVs, fans, and other electronic devices emitting speech, music, or noise should be off, if at all possible.

Distance between the child’s ear and the source of noise increases reverberation. This also negatively impacts children who use hearing devices. The ideal way to offset the problematic issue of distance is to use a remote microphone system (Thompson et al, 2020). Remote mics deliver the sound source or speech directly to the child’s device microphones.

When remote microphones or blue tooth technology are not available, then the caregiver “talks within earshot.” This means the speaker is on the child’s “better hearing side,” speaking within six inches or 15 centimetres of the child’s microphone (Rhoades, 2011). Listening to spoken language within earshot can dramatically increase speech audibility for any hearing device user.

- Acoustic highlighting: Sometimes referred to as consonant or envelope enhancement, this general strategy enhances speech audibility (Smith & Levitt, 1999). This renders perceptual salience to specific phonemes, morphological markers, or syntactic elements that the child appears not to hear, understand, or produce (Rhoades, 2011; Picheny, Durlach, & Braida, 1986).

- Auditory sandwich: This strategy is particularly effective for children transitioning from being primarily visual learners to auditory learners (Koch, 1999). As an example, the caregiver talks first; although the child heard it, the message was not understood. Therefore, the caregiver repeats what was said, but with visual cues (i.e., speechreading, print, pictures, or other visual aids) that enable the child to understand the message. This is auditory input first (listen only), followed by visual + auditory input (listen and look), then back to auditory-only input (listen only) as the last step. This sequential strategy familiarizes the child with what was heard so that comprehension through “hearing alone” is more readily attained (Rhoades, 2011).

- Auditory Bombardment: This strategy represents the idea of the provision of numerous opportunities for a child to hear different language targets in meaningful contexts during daily routines. Through auditory bombardment, a child gets a chance to listen over and over again to the same sounds, words, or language structures that may not have been heard due to lack of early auditory access (Encinas & Plante, 2016).

- Serve and return: Turn-taking is the foundation for developing spoken language communication. This strategy involves a caregiver being sensitive to the child’s needs, wants, and interests, and then responding accordingly. Such interactional exchanges facilitate maternal attachment, which is considered the foundation for meaningful learning (Day, 2007).

- Deliberate pausing: Often referred to as interactive silences, select types of self-controlled adult pausing can facilitate the language learning process. Deliberate pauses are acoustic silences that can precipitate child responses and can enhance speech perception (Yurovsky, et al, 2012). Some types of pauses are wait-time, think-time, the expectant pause, the impact pause, and the phrasal intraturn pause. Among the many advantages of adult controlled pauses are facilitating the child’s sustained auditory attention, promoting listening by bracketing meaningful language, encouraging the processing of linguistic units, nourishing contemplative and speculative thinking, informing the listener that a response is expected, providing the child with time to formulate a linguistic response, and promoting improved language production from the child (Rhoades, 2013).

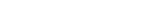

Creating opportunities for infant-directed speech

Let’s dig deeper into a three-year-old child’s life. A three-year-old can run, jump, ride a tricycle, kick a ball, hold a pencil in a preferred hand, and eat with a fork and spoon. Three-year-olds like to help adults in domestic activities, such as gardening and shopping. They are starting to learn the concept of sharing and are beginning social integration. Daily routines provide ample content to make the best use of infant-directed speech. For example, in Indian families, hot rotis (Chapattis) are served one by one during meals, hence the child can be involved in serving the rotis to each family member. This creates repeated opportunities for recognition of each family member’s name, and using possessives to identify whose roti it is. Pronouns and adjectives (“two rotis”) can be introduced, and concepts of hot, steam, and words for various tastes. All these can be well integrated into the child’s routine.

One of the most important things in children’s lives is play. Understanding the age and stage of the child’s play is important to make use of daily opportunities. Three-year-olds become more engaged socially with peers, which creates a wonderful opportunity to facilitate speech and language development. Through cooperative play, they learn to follow multiple directions and other complex language, such as the rules of a game. In India, “Gali Cricket” is a very popular bat and ball game. Children can learn the language of the game, the rules, and the number of players. Through team play, they also learn to understand the emotions of other players, to empathize, and to play with team spirit. Heightened emotions provide opportunities to focus on the varied pitch patterns of IDS (Barrett, et al, 2020).

Shared book reading is also an essential part of a child’s daily routine that is ideal for using IDS features, as parents use slower, more dramatic speech, varied intonation patterns, and larger vowel spaces when reading in character voices. As part of IDS, giving choices to children in selecting a book of their choice helps engage their attention and creates an abundance of opportunities for new vocabulary development. Children love folktales about animals, such as the Panchtantra in India. Involving children in making their own experience books is also an effective way of developing listening, language, speech, and literacy skills.

Music is a natural part of early childhood. It plays a vital role in enhancing auditory, language, and speech development. Children love to hear their favorite songs again and again. They love to dance with the rhythm and sing along with the lyrics. IDS can be applied to music by encouraging children to select their favorite songs and music, singing together, moving to the music, and playing instruments.

Self-advocacy skills as a foundation for using IDS

Appropriately-fitted hearing devices are the foundation necessary to make use of IDS. But beginning to wear their hearing device at three years of age and older may be very intimidating to children as they become aware that they are different from other children. Using IDS, parents can talk about the child’s devices, the manufacturer and model, and the names of the device parts during daily routines, as well as encouraging self-advocacy and helping children take responsibility for their devices (Flexer & Nakra, 2020). Developing these skills from the very beginning will give children self-confidence and the ability to talk about their devices and their hearing loss with their peers, as well as provide them with the auditory foundation to perceive IDS.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and intervention in children older than three years of age can be overwhelming for many families, but with the help of IDS, the process of developing spoken language communication through audition can be made more meaningful, motivating, and enjoyable.

Contributing author:

Hilda Furmanski, Fga., LSLS Cert. AVT, hildafur@gmail.com

Authors bios:

Ritu Nakra is a parent of a child with hearing loss. She also is a director of Hear Me Speak, an early intervention center based in Delhi; founder of AVTAR (Auditory-Verbal Trainer and Resources) mobile application and online session portal for parents and professionals; and co-founder of Online AVT. She has mentored numerous professionals and helped establish early intervention centres across India. She can be reached at ritunakra@rediffmail.com.

Mary McGinnis is the former director of the John Tracy Center Graduate Program, where she continues as faculty and grant mentor. She is also a LSL mentor and consultant. She can be reached at marydmcginnis@gmail.com.

Ellen A. Rhoades is an international consultant, mentor, researcher, and practitioner with 50 years of experience who has founded and/or established four auditory-verbal programs. Ms. Rhoades has co-authored/edited several books and has contributed to many book chapters and articles. She currently serves on review committees for six professional journals. She can be reached at ellenrhoades@gmail.com

For more information, please visit AG Bell here.

Aplicación del «habla dirigida a los niños» en la intervención de niños identificados de forma tardía

Ritu Nakra, B.Ed (HI), LSLS Cert.AVT; Mary D. McGinnis, LSLS Cert.AVT, PhD candidate; Ellen A. Rhoades, Ed.S., LSLS Cert.AVT

INTRODUCCIÓN

«Ah, ¿su hija no habla todavía? No se preocupe. Algunos niños empiezan a hablar más tarde que otros».

«El hermano de una amiga tardó en empezar a hablar».

Estos son algunos de los comentarios que los padres y madres reciben cuando su hija o hijo todavía no habla. No es frecuente que se les ocurra que pueda tener una pérdida auditiva.

Si bien existe un acuerdo generalizado de que la identificación temprana de la pérdida auditiva es importante en los efectos positivos a largo plazo, el cribado auditivo neonatal e infantil todavía no se ha implementado en todos los países (Singh, 2015). Es frecuente que un niño reciba un diagnóstico después de que alguna persona de la familia observe que no habla o no reacciona a los sonidos. Esta observación suele ocurrir cuando el niño tiene dos años o más. Si el niño tiene una pérdida auditiva de moderada a severa, la identificación se puede retrasar hasta que tiene tres o cuatro años. Considerando que los progenitores del 90-95% de los niños con una pérdida auditiva neurosensorial tienen una audición normal, la pérdida auditiva suele ser lo último que se esperan.

Niños con un diagnóstico tardío: una emergencia neurológica

El cerebro es el órgano principal de la audición. Los oídos son solo el punto de acceso, una «entrada» a través de la cual el sonido llega al cerebro. Dado que el habla y la comprensión del lenguaje hablado son eventos acústicos, la audición es el sentido más natural, directo y eficaz para aprender las habilidades de comunicación típicas. En general, las habilidades básicas de la escucha y el lenguaje se desarrollan durante los dos primeros años de vida, cuando el cerebro tiene una plasticidad neuronal máxima (Kuhl, 2011).

La pérdida auditiva en los dos primeros años de vida tiene como consecuencia cambios cerebrales significativos. Se produce una reorganización intermodal, lo que significa que el cerebro deja de recurrir a la información auditiva en favor de la información visual, algo que puede perjudicar el desarrollo de cualquier capacidad auditiva residual (Campbell y Sharma, 2016). Cuando el cerebro se reorganiza, desaparecen los procesos típicos del desarrollo de las habilidades de escucha y lenguaje hablado (LSL, por sus siglas en inglés). En ese momento, la pérdida auditiva pasa a ser un problema de «entrada» (Flexer y Rhoades, 2016).

Cuando el niño recibe un diagnóstico a una edad más tardía, es frecuente que la familia sufra una gran crisis emocional (Phillips, Worley y Rhoades, 2010). Se ha perdido el periodo principal de crecimiento infantil típico del habla y el lenguaje, y se han alterado los procesos de desarrollo típicos. Por este motivo, es necesario que los niños a los que se identifica de una manera tardía y sus cuidadores aprendan habilidades de LSL con la ayuda de especialistas en LSL que tengan experiencia en la aplicación de estrategias auditivo-verbales. Cuando la intervención basada en la audición se inicia a una edad posterior a los dos años, los especialistas en LSL aplican estrategias correctivas de intervención basada en la audición en el caso de niños con deficiencias auditivas.

Retos adicionales de los niños de mayor edad

Son numerosas las áreas de desarrollo que dependen de la audición y la adquisición del lenguaje. Algunas de estas áreas incluyen conocimientos académicos y habilidades socioemocionales, entre ellas, la Teoría de la mente (Ketalaar et al, 2012). Para salvar las brechas de aprendizaje, las prácticas auditivo-verbales (una intervención holística) incorporan las características del habla dirigida a los niños (HDN) para facilitar la atención auditiva centrada y sostenida, así como el aprendizaje del lenguaje hablado. El HDN fomenta una base auditiva sólida que, a su vez, posibilita la incorporación de muchos niños en el sistema educativo ordinario, que les permitirá desarrollar las habilidades típicas de la lectoescritura (Mayer y Trezak, 2018).

¿Puede el HDN mejorar la reorganización intermodal?

¿Se puede revertir la reorganización intermodal en el caso de niños que reciban una entrada auditiva adecuada a una edad más tardía? Existen trabajos de investigación en los que se indica que es posible modificar o mitigar la reorganización cortical en adultos, incluso después de largos periodos de sordera (Stropahl, Chen y Debener, 2017). Cuando los cuidadores emplean el HDN, en los trabajos de investigación se reflejan mejoras en el aprendizaje del lenguaje de los niños (Wang et al, 2017). Se aprecian mejoras en las habilidades de atención auditiva del niño que, a su vez, estimulan las capacidades de aprendizaje estadístico que se consideran esenciales para el aprendizaje del lenguaje.

El HDN es un estilo interactivo de habla dirigida a los niños en el que se utilizan palabras más sencillas, mucha repetición, un rango de tono más alto y variado, y una velocidad de habla más lenta (Rhoades, 2020a; Rhoades, 2020b). Los cuidadores de las culturas occidentales suelen utilizar con los niños pequeños este tipo exagerado de «turno de habla» con carga emocional. En las conclusiones de los trabajos de investigación se indica que en los componentes del HDN se resaltan determinados aspectos del habla (p. ej., un énfasis en la frecuencia fundamental y un mayor espacio vocal), lo que se traduce en que estos componentes sean más destacados en el aprendizaje auditivo (Bornstein et al., 2020).

El HDN puede ayudar a los niños en la transición del procesamiento visual al procesamiento auditivo (Dilley et al, 2020). Afortunadamente, existe una coincidencia perfecta entre los componentes del HDN y las estrategias auditivo-verbales que utilizan los especialistas en LSL y que proporcionan la base para la intervención, independientemente de la edad del niño. Las estrategias que se utilizan con un niño identificado a una edad tardía son similares a las que se utilizan con un niño identificado a una edad más temprana, exceptuando que es probable que las oportunidades diarias para que los progenitores utilicen el HDN se deban planificar de una manera más reflexiva, dado que los niños de mayor edad no pasarán tanto tiempo con ellos como pasan en el centro educativo o con los amigos. Para fortalecer la base auditiva se deben maximizar las oportunidades de desarrollo de la escucha, el lenguaje y el habla. En comparación con los niños identificados a una edad temprana, los niños más mayores suelen necesitar más tiempo en la transición del procesamiento visual al auditivo.

Estrategias de LSL para utilizar el HDN con niños de mayor edad

Mediante las estrategias de LSL (Fickenscher, Gaffney y Dickson, 2015), los componentes del HDN se hacen audibles para los niños identificados a una edad tardía.

- Minimizar las condiciones de escucha adversas: Un ruido de fondo excesivo hace que los entornos acústicos sean más complejos, lo que degrada significativamente la percepción del habla, la comprensión del lenguaje y las habilidades cognitivas como la atención auditiva y la velocidad de procesamiento (McMillan y Saffran, 2016; Blaiser et al, 2014). Además, las condiciones de escucha adversas aumentan significativamente la necesidad de esforzarse para escuchar, lo que puede resultar agotador para los niños con una pérdida auditiva (Peng y Wang, 2019).

Determinadas modificaciones ambientales (p. ej., alfombras y cubiertas de tela en ventanas y muebles rígidos) ayudan a amortiguar la reverberación. Los televisores, ventiladores y otros dispositivos electrónicos que emitan voces, música o ruido deben estar apagados, si es posible.

La distancia entre el oído del niño y la fuente de ruido incrementa la reverberación. Afecta también negativamente a los niños que utilizan dispositivos auditivos. Para contrarrestar el problema de la distancia, lo ideal es utilizar un sistema de micrófono remoto (Thompson et al, 2020). Los micrófonos remotos transmiten la fuente de sonido o el habla directamente a los micrófonos del dispositivo del niño.

Cuando los micrófonos remotos o la tecnología bluetooth no se encuentren disponibles, el hablante debe hablar «al alcance del oído», lo que significa que se debe situar en el «lado de mejor audición» y hablar a 15 centímetros del micrófono del niño (Rhoades, 2011). La escucha del lenguaje hablado «al alcance del oído» puede aumentar enormemente la audibilidad del habla de cualquier usuario de dispositivos auditivos.

- Resaltado acústico: Esta estrategia general que, en ocasiones, se denomina mejora de consonantes o envolventes, mejora la audibilidad del habla (Smith y Levitt, 1999). Se otorga una relevancia perceptual a fonemas específicos, marcadores morfológicos o elementos sintácticos que el niño parece no oír, comprender o producir (Rhoades, 2011; Picheny, Durlach y Braida, 1986).

- Sándwich auditivo: Esta estrategia es particularmente eficaz en el caso de los niños que pasan de ser aprendices visuales principalmente a aprendices auditivos (Koch, 1999). A modo de ejemplo, supongamos que el cuidador habla primero y, aunque el niño le oiga, no entiende el mensaje. En este caso, el cuidador repite lo que haya dicho pero empleando señales visuales (por ejemplo, lectura labial, texto impreso, imágenes u otras ayudas visuales) que permiten que el niño comprenda el mensaje. Esta estrategia secuencial se compone de una entrada auditiva en primer lugar (solo escuchar), seguida de una entrada visual + auditiva (escuchar y mirar) y, como último paso, una entrada solo auditiva (solo escuchar). De esta manera, el niño se familiariza con lo que haya oído, de manera que la comprensión a través de «solo oír» se logra con mayor facilidad (Rhoades, 2011).

- Bombardeo auditivo: Esta estrategia se basa en la idea de facilitar numerosas oportunidades para que un niño oiga diferentes elementos del lenguaje en contextos significativos durante las rutinas cotidianas. A través del bombardeo auditivo, un niño tiene la oportunidad de escuchar una y otra vez los mismos sonidos, palabras o estructuras del lenguaje que quizá no haya oído debido a la falta de un acceso auditivo temprano (Encinas y Plante, 2016).

- Emitir y responder: La intervención por turnos es la base para desarrollar la comunicación del lenguaje hablado. Esta estrategia implica que un cuidador sea sensible a las necesidades, los deseos y los intereses de un niño y, a continuación, responda en consonancia. Estos intercambios interactivos facilitan el apego materno, que se considera la base para un aprendizaje significativo (Day, 2007).

- Pausas deliberadas: Denominados a menudo silencios interactivos, determinados tipos de pausas autocontroladas por parte de un adulto pueden facilitar el proceso de aprendizaje del lenguaje. Las pausas deliberadas son silencios acústicos que pueden propiciar las respuestas de un niño y mejorar la percepción del habla (Yurovsky, et al, 2012). Entre los tipos de pausas se encuentran el tiempo de espera, el tiempo de reflexión, la pausa expectante, la pausa de impacto y la pausa intraturno oracional. Entre las numerosas ventajas de las pausas controladas por un adulto se encuentran el fortalecimiento de la atención auditiva sostenida del niño, la potenciación de la escucha mediante el uso de un lenguaje significativo, el fomento del procesamiento de unidades lingüísticas, el refuerzo del pensamiento contemplativo y especulativo, la información al oyente de que se espera una respuesta, la facilitación al niño de tiempo para que formule una respuesta lingüística y el fomento de la mejora de la producción del lenguaje por parte del niño (Rhoades, 2013).

Creación de oportunidades para el habla dirigida a los niños

Analicemos la vida de un niño de tres años. A esta edad puede correr, saltar, montar en triciclo, golpear con el pie una pelota, sostener un lápiz con su mano preferida y comer con tenedor y cuchara. A los niños de tres años les gusta ayudar a los adultos en las actividades domésticas, como la jardinería y las compras. Están comenzando a aprender el concepto de compartir y se están empezando a integrar socialmente. Las rutinas diarias facilitan un contenido amplio para poner en práctica el mejor uso del habla dirigida a los niños. Por ejemplo, en las familias indias, los rotis (chapatis) calientes se sirven uno por uno durante las comidas, por lo que el niño puede participar en servir los rotis a cada miembro de la familia. De esta manera, se crean oportunidades repetidas para el reconocimiento del nombre de cada miembro y el uso de posesivos para identificar de quién es el roti. Se pueden introducir pronombres y adjetivos («dos rotis»), conceptos de caliente y vapor, y palabras de diversos sabores, que se puede integrar perfectamente en la rutina del niño.

Uno de los aspectos más importantes de la vida infantil es el juego. La comprensión de la edad y la etapa de juego de un niño es importante para aprovechar las oportunidades diarias. Los niños de tres años mantienen una mayor interacción social con otros niños, lo que genera una gran oportunidad para facilitar el desarrollo del habla y el lenguaje. A través del juego colaborativo, aprenden a seguir múltiples instrucciones y otro lenguaje complejo, como son las reglas de un juego. En la India, «Gali Cricket» es un juego de bate y pelota muy popular. Los niños pueden aprender el lenguaje del juego, las reglas y el número de jugadores. A través del juego en equipo, aprenden también a entender las emociones de otros jugadores, a empatizar y a jugar con un espíritu de equipo. Las emociones intensificadas ofrecen oportunidades para centrarse en los diversos patrones de tono del HDN (Barrett, et al, 2020).

La lectura compartida de un libro es también una parte esencial de la rutina diaria de un niño y es idónea para utilizar los componentes del HDN, dado que los progenitores emplean un habla más lenta y dramática, diversos patrones de entonación y espacios vocales mayores cuando leen poniendo voces a los personajes. Como parte del HDN, la facilitación de opciones a los niños para que seleccionen el libro que prefieran ayuda a captar su atención y genera una gran cantidad de oportunidades para desarrollar un nuevo vocabulario. A los niños les encantan las fábulas sobre animales, como el Panchtantra en la India. La creación de sus propios libros de experiencias es también una manera eficaz de desarrollar las habilidades de escucha, lenguaje, habla y lectoescritura.

La música es un componente natural de la primera infancia. Desempeña un papel esencial en la mejora del desarrollo auditivo, el lenguaje y el habla. A los niños les encanta escuchar sus canciones preferidas una y otra vez. Les gusta bailar siguiendo el ritmo y cantando la letra. El HDN se puede aplicar a la música animando a los niños a que seleccionen sus canciones y su música preferidas, cantando juntos, bailando al ritmo de la música y tocando instrumentos.

Habilidades de defensa de los propios intereses como base para utilizar el HDN

Unos dispositivos auditivos debidamente ajustados son la base necesaria para poner en práctica el HDN. Sin embargo, empezar a utilizar dispositivos auditivos a los tres años o más tarde puede resultar bastante intimidante, ya que los niños se dan cuenta de que son diferentes al resto. Utilizando el HDN, los progenitores pueden hablar de los dispositivos auditivos del niño, del fabricante, del modelo y de los nombres de las partes durante las rutinas diarias, además de fomentar la defensa de los propios intereses y ayudarle a que asuma la responsabilidad de sus dispositivos (Flexer y Nakra, 2020). El desarrollo de estas habilidades desde un principio les aportará a los niños confianza en sí mismos y la capacidad de hablar de sus dispositivos y de su pérdida auditiva con sus compañeros, además de proporcionarles la base auditiva para percibir el HDN.

Conclusión

El diagnóstico y la intervención en el caso de niños mayores de tres años pueden resultar abrumadores para muchas familias pero, con la ayuda del HDN, el proceso de desarrollo de la comunicación del lenguaje hablado a través de la audición puede ser más significativo, estimulante y agradable.

Autora colaboradora:

Hilda Furmanski, Fga., LSLS Cert. AVT, hildafur@gmail.com

Biografía de las autoras:

Mary McGinnis es exdirectora del Programa de Graduados del John Tracy Center, donde continúa como docente y tutora de becas. Es también tutora y consultora de LSLT. Se le puede contactar en marydmcginnis@gmail.com.

Ellen A. Rhoades es consultora internacional, tutora, investigadora y profesional en ejercicio con 50 años de experiencia que ha fundado y/o establecido cuatro programas auditivo-verbales. La Sra. Rhoades es coautora/editora de varios libros y ha contribuido a numerosos capítulos y artículos de libros. Actualmente forma parte de comités de revisión en seis revistas profesionales. Se le puede contactar en ellenrhoades@gmail.com

Ritu Nakra es madre de un niño con pérdida auditiva. Es también directora de Hear Me Speak, un centro de intervención temprana con sede en Delhi; es fundadora de la aplicación móvil AVTAR (Auditory-Verbal Trainer and Resources) y de un portal de sesiones en línea para progenitores y profesionales; y es cofundadora de Online AVT. Ha sido tutora de numerosos profesionales y ha ayudado a establecer centros de intervención temprana en toda la India. Se le puede contactar en ritunakra@rediffmail.com.

Para mas infomación, visite a AG Bell International aquí.

References / Referencias bibliográficas

Barrett, K. C, Chatterjee M., Caldwell, M. T., Deroche, M.L.D., Jiradejvong, P., Kulkarni, A. M. & Limb, C. J. (2020). Perception of child-directed versus adult-directed emotional speech in pediatric cochlear implant users. Ear & Hearing, 2020 Sep/Oct: 41(5): 1372-1382. PMID 32149924 DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000862

Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., Bohr, Y., Abdelmaseh, M. Lee, C. Y. & Espositio, G. (2020). Maternal sensitivity and language in infancy each promotes child core language skill in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2nd Quarter, 51: 483-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.01.002

Blaiser, K. M., Nelson, P. B., & Kohnert, K. (2014). Effect of repeated exposures on word learning in quiet and noise. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 37, 25–35.

Campbell, J. and Sharma, A. (2016). Visual cross-modal re-organization in children with cochlear implants. PLoS ONE 11(1): e0147793.

Day, C. (2007) Attachment and early language development: Implications for early intervention, NHSA Dialog, 10:3-4, 143-150, DOI: 10.1080/15240750701741637

Dilley, L., Lehet, M., Wieland, E. A., Arjmandi, M. K., Kondaurova, M., Wang, Y., Reed, J., Svirsky, M., Houston, D., & Bergeson, T. (2020). Individual differences in mothers’ spontaneous infant-directed speech predict language attainment in children with cochlear implants. JSLHR, 63(7), 2453–2467. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-19-00229

Encinas, D. and Plante, E. (2016). Feasibility of a recasting and auditory bombardment treatment with young cochlear implant users. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 47(2): 157-170.

Fickenscher, S. & Salvucci, D. (2016) Chapter 7. E-book: An introduction to educating children who are deaf/hard of hearing

Fickenscher, S., Gaffney, E., and Dickson, C. (2015). Auditory verbal strategies to build listening and spoken language skills. https://www.mcesc.org/docs/building/3/av%20strategies%20to%20build%20listening%20and%20spoken%20language%20skills%20(1).pdf?id=1107

Flexer, C. and Nakra, R. (2020). Guiding the development of specific self-advocacy skills in very young children with hearing loss: A family focus. Volta Voices, October 22, 2020. https://agbellvoltavoices.com/guiding-the-development-of-specific-self-advocacy-skills-in-very-young-children-with-hearing-loss-a-family-focus/

Flexer, C. & Rhoades, E. A. (2016). Hearing, listening, the brain, and auditory-verbal therapy (pp. 23-22). In W. Estabrooks, K. MacIver-Lux, and E. A. Rhoades (Eds.), Auditory-verbal therapy: For young children with hearing loss and their families and the practitioners who guide them. San Diego, CA: Plural.

Ketelaar, L. Rieffe, C., Wiefferink, M. A., Johan, H. M., Frijns, M. D. (2012. Does hearing lead to understanding? Theory of mind in toddlers and preschoolers with cochlear implants, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(9): 1041–1050, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss086

Koch, M. E. (1999). Bringing sound to life: Principles and practices of cochlear implant rehabilitation. Bethesda, MD: York Press.

Kuhl P. K. (2011). Early language learning and literacy: Neuroscience implications for education. Mind, brain and education: International Mind, Brain, and Education Society, 5(3), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2011.01121

McMillan B.T. & Saffran J.R. (2016). Learning in complex environments: The effects of background speech on early word learning. Child Development, Nov;87(6):1841-1855. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12559

Mayer, C., & Trezek, B. J. (2018). Literacy Outcomes in Deaf Students with Cochlear Implants: Current State of the Knowledge. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 23(1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enx043

Peng, Z.E. & Wang, L. M. (2019). Listening effort by native and non-native listeners due to noise, reverberation, and talker foreign accent during English speech perception. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62, 1068-1081. DOI: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-H-17-0423

Phillips, R., Worley, L. & Rhoades, E.A. (2010). Socioemotional considerations. In E.A. Rhoades and J. Duncan [Eds.], Auditory-verbal practice: Toward a family-centered approach (pp 187-224). Springfield IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Picheny, M. A., Durlach, N. I., & Braida, L. D. (1986). Speaking clearly for the hard of hearing. II: Acoustic characteristics of clear and conversational speech. Journal of speech and hearing research, 29(4), 434–446. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.2904.434

Rhoades, E. A. (2011). Listening strategies to facilitate spoken language learning among signing children with cochlear implants (pp.142-171). In R. Paludneviciene and I. W. Leigh (Eds.). Cochlear implants: Evolving perspectives. Washington DC: Gallaudet.

Rhoades, E.A. (2013). Interactive silences: Evidence for strategies to facilitate spoken language in children with hearing loss. Volta Review, 113(1), 57-73.

Rhoades, E. A. (2020a). How infants learn, Part I. Volta Voices, Jan-Mar 2020.

Rhoades, E. A. (2020b). How infants learn language, Part II. Volta Voices, Jul 29, 2020.

Singh, V. (2015). Newborn hearing screening: Present scenario. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 40(1): 62–65. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.149274

Smith, L.Z., & Levitt, H. (1999). Consonant enhancement effects on speech recognition of hearing-impaired children. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 10(8), 411-21.

Stropahl, M., Chen, L-C, and Debener, S. (2017). Cortical reorganization in post-lingually deaf cochlear implant users: Intra-modal and cross-modal considerations. Hearing Research 343: 1280137.

Thompson, E.C., Benítez-Barrera, C.R.. Angley, G.P., T. Woynaroski, T. & Tharpe, A.M. (2020). Remote microphone system use in the homes of children with hearing loss: Impact on caregiver communication and child vocalizations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(2): 633-642. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00197

Wang X, Liang M, Zhang J, Huang H, Zheng Y. (2017). Research on cortical cross-modal reorganization of children with congenital severe deafness after cochlear implant. Journal of Biomedical Engineering, 34, 667-673.

Yurovsky D., Yu, C. and Smith, L. B. (2012). Statistical speech segmentation and word learning in parallel: scaffolding from child-directed speech. Frontiers in Psychology, 3:374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00374