Percival J. Dunham and his staff at the Instituto Oral Modelo.

Written By: Calli Barker Schmidt

It’s been a challenging year for parents, educators and children as the Covid-19 pandemic has forced them from their brick-and-mortar schools into full-time virtual learning. Nearly a year into the first shutdowns, many children have yet to return to the classroom.

Listening and Spoken Language (LSL) therapists and their clients have pointed out the additional barriers to effective communication instruction: from masks that make it difficult, if not impossible, to lip read to restrictions on regular in-home visits to guard against transmission of the virus.

In Latin American countries where LSL has advanced at a limited rate, the barriers can be even higher. Yet while the challenges are great, conversations with some professionals reveal a silver lining in some of the pandemic workarounds, including the rise of online instruction as a therapeutic tool.

Schools in Argentina, Peru, Chile and Paraguay have transitioned into online learning or part-time in-person instruction, and in some cases have closed completely.

For most of the past year, Chilean students were taught remotely and then transitioned to a reduced schedule of in-school instruction, says Nora Gardilcic, LSLS Cert. AVT. Auditory-verbal therapy was offered only online during the lockdown, but “now you can see kids at home or in private practice,” but not in schools or hospitals.

Mexico is one of the countries hardest hit by the pandemic. Of the country’s 32 states, only two have been able to maintain regular in-person classroom instruction, says Dr. Lilian Flores-Beltrán, LSLS Cert. AVT. “Obviously, the few schools we have in this country for the deaf are closed,” she says. “However, there are [a few] professionals who have continued their services with good results through telepractice.”

Unfortunately, there are only three certified LSL specialists in the country. “Many professionals ‘say’ they work through auditory-verbal therapy, but they do not teach… children [who are deaf and hard-of-hearing] to listen,” says Flores-Beltrán. “They use outdated methodologies and lip-facial reading.”

The solution, says Flores-Beltrán and other LSL specialists, is complicated. There needs to be more access to training, and that training has to be in Spanish so more professionals can take advantage of it.

“We need good and updated resources adapted—not just translated—to Spanish,” says Percival J. Dunham, general director of the Instituto Oral Modelo in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Flores-Beltrán agrees. Professionals need “material in Spanish that simultaneously helps them with ideas and suggestions with their training and their mentoring,” she says. “We need to train more professionals.”

“There are a lot of professionals here in Chile who do an amazing job using the auditory approach,” says Gardilcic. “But they don’t become certified because it’s expensive, the tests are in English and most of the books to study [for certification] are in English.”

Teresita Mansilla, LSLS Cert. AVT, agreed. “I am the only certified AVT in Paraguay. It would be great if the students could get more information in Spanish and better access to get lessons in Spanish.”

As in the United States, therapists and other professionals have had to refine and even reinvent their approaches to children who are deaf or hard of hearing and their families as Zoom and Facetime sessions have largely replaced in-person instruction and assistance.

It has not gone smoothly for a number of families. “Not all parents have access to the internet. They have mobile phones, but they have to buy airtime” to use some applications, such as Zoom, for orientation and instruction, says Flores-Beltrán. “For those parents with limited resources, I ask them for three or four video clips [of their children] doing an activity where they can show me some objectives achieved, and then I call them [back] to give them feedback and propose new objectives.

“Obviously, this is not the same as when I treat them face to face, but I try to give a lot of coaching to continue to empower the parents so they do not feel frustrated,” she says.

Where internet access is not a problem, therapists have rolled with the punches. “At Instituto Oral Modelo, we worked during the quarantine 100 percent online, and we didn’t find significant changes with teletherapy, [although] more family involvement was required,” says Denham.

“For the children who were just diagnosed, it was harder. I think their parents needed more live demonstration,” says Gardilcic. “For the others, they kept moving forward as usual.”

In fact, some therapists see online options as a boon to their practices. “The pandemic never affected the LSL sessions,” says Mansilla. “On the contrary, I could see that families were more active and creative with their children.”

Online games and activities in which professionals and families can interact can supplement the use of toys and materials that parents have on hand for the online sessions, says Hilda Furmanski, LSLS Cert. AVT in Buenos Aires.

“I feel telepractice has empowered parents and as a therapist, there is more coaching and I feel okay with that,” Furmanski says. “It’s made me change my thoughts about remote therapy. I would love in the future to keep it this way and see the families in the office once a month.”

For more information, please visit AG Bell here.

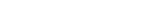

Left to Right: Hilda Furmanski, Nora Gardilcic, and Percival J. Dunham alongside Emilio Alonso-Mendoza

Los retos en LSL por la pandemia en Latinoamérica

Este año ha sido un reto para los padres, los educadores y los alumnos, ya que la pandemia de la Covid-19 les ha obligado a abandonar las escuelas tradicionales y centrarse en el aprendizaje virtual a tiempo completo. Casi un año después de los primeros cierres, muchos niños y niñas todavía no han regresado a las aulas.

Los terapeutas de LSL (siglas en inglés de Escucha y Lenguaje Hablado) y sus clientes han destacado las barreras adicionales en la enseñanza de una comunicación eficaz: desde las mascarillas que dificultan, si no imposibilitan, la lectura de los labios hasta restricciones en las visitas domiciliarias periódicas para protegerse de la transmisión del virus.

En los países latinoamericanos donde el enfoque LSL ha avanzado a un ritmo limitado, las barreras pueden ser todavía mayores. Sin embargo, si bien los retos son considerables, las conversaciones con algunos profesionales revelan un lado positivo en algunas de las soluciones frente a la pandemia, incluido el aumento de la enseñanza en línea como herramienta terapéutica.

Las escuelas de Argentina, Perú, Chile y Paraguay se han pasado al aprendizaje en línea o a la enseñanza presencial a tiempo parcial y, en algunos casos, han cerrado por completo.

Durante la mayor parte del año pasado, los alumnos chilenos recibieron las clases de forma remota y, a continuación, pasaron a tener un horario reducido de enseñanza presencial, explica Nora Gardilcic, TAV certificada en LSLS. La terapia auditivo-verbal se ofreció únicamente en línea durante el confinamiento, pero «actualmente se puede atender a los niños en el domicilio o en consultas privadas», pero no en escuelas ni en hospitales.

México es uno de los países más afectados por la pandemia. De los 32 estados del país, solamente en dos se ha podido mantener la enseñanza presencial en las aulas, informa la Dra. Lilian Flores-Beltrán, TAV certificada en LSLS. «Obviamente, las pocas escuelas que tenemos en este país para niños con sordera están cerradas», añade. «No obstante, hay [algunos] profesionales que han continuado prestando sus servicios con buenos resultados a través de la telepráctica».

Lamentablemente, en el país solo existen tres especialistas certificados en LSL. «Muchos profesionales “dicen” que trabajan utilizando la terapia auditivo-verbal, pero no enseñan… a los niños [con sordera e hipoacusia] a escuchar», asegura la Dra. Flores-Beltrán. «Utilizan metodologías anticuadas y lectura labial».

La solución, en su opinión y en la de otros especialistas en LSL, es complicada. Debe existir un mayor acceso a la formación, que debe ser en español para que un mayor número de profesionales pueda aprovecharla.

«Necesitamos recursos adaptados de calidad y actualizados, no solo traducidos, al español», afirma Percival J. Dunham, director general del Instituto Oral Modelo de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

La Dra. Flores-Beltrán se muestra de acuerdo. Los profesionales necesitan «material en español que les ayude simultáneamente con ideas y sugerencias sobre su formación y su tutoría», añade. «Necesitamos que se formen más profesionales».

«En Chile existen numerosos profesionales que realizan un trabajo excelente utilizando el enfoque auditivo», destaca la Sra. Gardilcic. «Sin embargo, no obtienen la certificación porque es cara, las pruebas están en inglés y la mayoría de los libros de estudio [para la certificación] también está en inglés».

Teresita Mansilla, TAV certificada en LSLS, se muestra de acuerdo. «Soy el único TAV certificado en Paraguay. Sería estupendo que los estudiantes pudieran obtener más información en español y un mejor acceso para recibir lecciones en español».

Al igual que en los Estados Unidos, los terapeutas y otros profesionales han tenido que perfeccionar e incluso reinventar sus enfoques con los niños con sordera o hipoacusia y sus familias, de manera que las sesiones de Zoom y FaceTime han reemplazado en gran medida la enseñanza y la asistencia presenciales.

Para numerosas familias el proceso no ha sido fácil. «No todos los padres tienen acceso a Internet. Disponen de teléfonos móviles, pero deben comprar “tiempo de conexión” para usar algunas aplicaciones, como Zoom, para recibir orientación y enseñanza», dice la Dra. Flores-Beltrán. «En el caso de los padres con recursos limitados, les solicito tres o cuatro videoclips [de sus hijos] realizando una actividad en la que me puedan mostrar algunos objetivos alcanzados y, a continuación, les llamo para facilitarles feedback y proponerles nuevos objetivos.

«Obviamente, no es lo mismo que cuando les atiendo presencialmente, pero imparto bastante coaching para seguir empoderando a los padres y que no se sientan frustrados», añade.

Donde el acceso a Internet no es un problema, los terapeutas se han adaptado a la situación. «En el Instituto Oral Modelo trabajamos durante la cuarentena en línea al cien por cien y no encontramos diferencias significativas con la teleterapia, [si bien] fue precisa una mayor participación familiar», indica la Sra. Denham.

«En el caso de los niños con un diagnóstico reciente, fue más complicado. Creo que sus padres necesitaban más demostración en vivo», destaca la Sra. Gardilcic. «En el caso del resto, siguieron progresando de la manera habitual».

De hecho, algunos terapeutas consideran que las opciones en línea son una bendición para sus prácticas. «La pandemia nunca ha afectado a las sesiones de LSL», dice la Sra. Mansilla. «Por el contrario, he podido apreciar que las familias se mostraban más activas y creativas con sus hijos».

Los juegos y las actividades en línea en los que los profesionales y las familias interactúan pueden complementar el uso de juguetes y materiales que los padres tengan a mano para las sesiones en línea, asegura Hilda Furmanski, TAV certificada en LSLS, en Buenos Aires.

«Creo que la telepráctica ha empoderado a los padres y, como terapeuta, debo facilitar más coaching y me parece bien», añade la Sra. Furmanski. «Ha hecho que cambie lo que pensaba de la terapia remota. Me encantaría que se mantuviera en el futuro de esta manera y atender a las familias en la consulta una vez al mes».

Para mas infomación, visite a AG Bell International aquí.